Facebook Wants Your Real Name — Even If It Means Outing You

Just days after Google announced it would no longer police the names chosen by users on its social network, Facebook decided to take up the battle cry, stressing a name policy it’s had on the books but rarely enforced until now.

“Facebook is a community where people use their real identities. We require everyone to provide their real names, so you always know who you’re connecting with. This helps keep our community safe,” says the popular social network on their recently-edited name policy page, which tells users to list “your real name as it would be listed on your credit card, driver’s license or student ID.”

The policy is meant to cover all users, but — much like it happened with Google’s similar policy — it’s overwhelmingly impacting people whose names don’t look sufficiently “real.” A person going by John Smith is unlikely to trigger review, whereas someone named Violet Blue (which is, by the way, her legal name), is much more likely to do so. Partly because of this, drag performers whose names tend to fall short of the “real”-looking name criteria currently appear to have been singled out by Facebook’s name policy-enforcement squad.

Miz Cracker, a performer and contributor to Slate, told Slate’s J. Bryan Lowder that at least 20 performers in her network have had their profiles suspended. TechCrunch has the number in the hundreds, though no single definitive list exists.

“I’ve been Sister Roma for 27 years,” said the performer and member of the well-known LGBT-rights advocacy group Sisters of Perpetual Indulgence, Sister Roma, in an interview with Ars Technica. “If you ask anyone my name, in or out of drag, they will tell you it’s Roma. Is it the name on my driver’s license? No. But it is my name.”

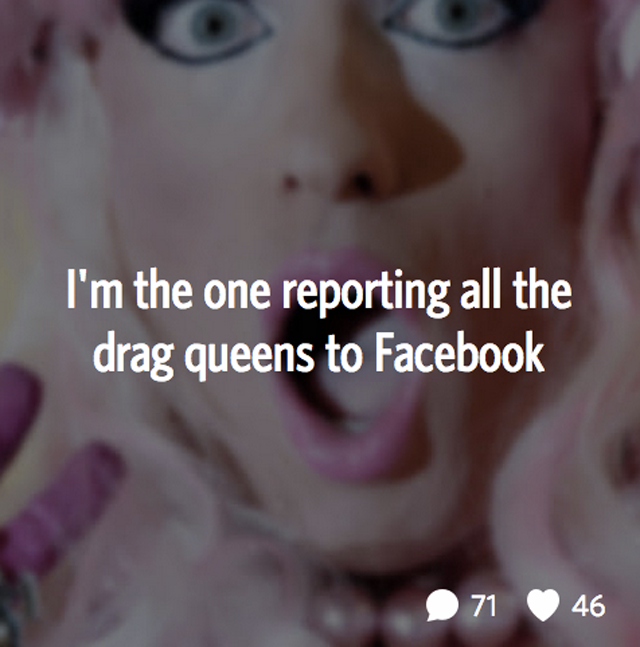

A far more worrisome mechanism within what’s being called a “drag queen dragnet,” is Facebook’s insistence that users tell on those they believe aren’t using their real names. It’s very easy to see how such a reporting mechanism may be abused in order to remove any individual whose identity doesn’t match what the mainstream considers acceptable.

“Given the high number of queens being ‘hit hard,’ as Miz Cracker put it, someone has clearly made a serious project of reporting drag profiles to (or perhaps from within) the company,” Lowder writes.

Robyn Pennacchia at Death and Taxes agrees, “Given the proliferation of non-legal names used on Facebook by non-drag queens and cisgendered people just trying to be whimsical, it seems as though these communities have been specifically and unfairly targeted.”

Lending credence to these allegations, last week TechCrunch posted a screenshot of a post on the anonymous network Secret from someone claiming to be targeting drag queens for names policy violations on Facebook.

When Slate reached out to the giant network, Facebook acknowledged that their suspensions were a response to reports of name violations made by other users. However, Facebook soon began to backpedal, telling TechCrunch three days later that suspensions were the result of an algorithm that had “discovered the drag queens.” To date, none of the married couples I know who have a single Facebook profile with a mishmash or portmanteau of their names seem to have been affected, giving weight to the suggestion that specific groups are being targeted.

Intent doesn’t matter

This policy stands in direct opposition to Facebook’s February move to include 56 gender options on its profiles. One’s driver’s license may not list one as “gender fluid,” and that’s okay with Facebook. And as Violet Blue points out, Facebook was well represented at San Francisco Pride in June — so it may not be intentional discrimination so much as its far more insidious twin, clueless privilege.

Ultimately, whether or not Facebook is targeting drag performers doesn’t matter. They’ve erected a mechanism that enables anyone who wishes to target a vulnerable population to do so, and they are enforcing a policy that will cause harm no matter how well-intended.

There are a number of excellent reasons a person may choose to use a pseudonym online, the most obvious being ensuring personal safety and control over how much personal information is made publicly available and when. In this age of increasingly targeted online abuse against women, minorities, LGBTQ individuals, and just about anyone who has the audacity to speak out against the status quo, the ability to create a separate identity so people can speak their truth and still sleep at night without fearing for their lives is a nontrivial thing.

The answer is not to force everyone to give their legal names — especially when the people being forced to go first are overwhelmingly members of a group that faces such an extraordinary amount of violence, discrimination and abuse already.

“Not everyone is safer by giving out their real name,” writes social media researcher danah boyd. “Quite the opposite; many people are far less safe when they are identifiable. And those who are least safe are often those who are most vulnerable.”

As drag performer Jeza Belle put it in a piece at the Huffington Post:

Gays, lesbians, bisexuals, and transgender people — and drag queens can often belong to more than one of these groups — know full well the difficulty that comes with coming out to the people with whom they are closest. For that reason many drag queens, while leading fulfilling lives both on- and offstage, have not let family members or employers in on the news of their alternate personae, as it’s a deeply personal and hard conversation to have — sometimes more difficult than coming out the first time.

Coming out as a drag queen has led to more than a few broken families, lost employment, and strained friendships. This is why, while cultivating relationships with individuals online using their stage name, not all queens are fully comfortable with letting certain family and friends into their world of drag. Facebook’s policy forces these queens to either choose between maintaining a social-media presence and risking losing their online support system and carefully balanced identities.

David Campos, a San Francisco-based attorney and member of the city’s Board of Supervisors, warned Facebook that its policy was likely to result in the opposite of what they seemed to intend.

“Facebook may not be aware that for many members of the LGBT community the ability to self-identify is a matter of health and safety,” Campos said in a statement. “Not allowing drag performers, transgender people and other members of our community to go by their chosen names can result in violence, talking, violations of privacy and repercussions at work.”

Scott Wiener, an LGBT advocate and another member of San Francisco’s Board of Supervisors, addressed the issue on his Facebook page last week: “While many drag queens are ‘out’ about who they are, not all drag queens have that luxury. Plenty of discrimination, hate, and violence toward the LGBT community still exists in many parts of the world, and various people have drag personas that they feel the need to keep separate from the rest of their lives. People who disclose their non-drag identity — and who, conversely, announce to the world that they are drag queens — should do so because they want to, not because Facebook is forcing them to do so in order to continue using their profiles.”

Facebook told the BBC that “its real-name policy was designed to protect the community and increase accountability,” but who’ll be held accountable when drag performers, trans individuals, sex workers and others suffer the social, emotional, psychological, economic, physical repercussions of being out on Facebook?

The cancer is spreading

“This is really about a lot more than just a bunch of drag queens bitching because we can’t use our stage names,” Sister Roma said to Ars Technica. “I’ve heard from women who are trying to escape an abusive relationship, sex workers, burlesque performers, and activists who don’t want their real names exposed for fear of discrimination in the workplace and trans people who have finally found peace with themselves and their sexual identity who are being forced to revert to names that they associate with a dark and dismal past. These are the messages that affect me the most.”

Indeed, the policy is beginning to ripple beyond the epicenter. The independent adult director and performer Julie Simone had her Facebook profile suspended for a names violation just days after Google Plus announced the end of their names policy. According to Simone, Facebook changed her account name to her legal name without her consent before locking her out of it for 30 days. This move effectively handed her legal identity to fans and stalkers alike, and outed her to any friend or family member who didn’t already know about her involvement in sex work. And it did so without her consent.

Enforcement escalated mid-September, and it’s only spreading. A week and a half ago, a Hawaiian user was locked out of his account because his middle name, Nahooikaikakeolamauloaokalani, didn’t appear sufficiently “real.” Over the weekend, the photographer Merkley was shut out of his Facebook account for a name violation as well.

Unlike many who face stigma or don’t have the means to do so, Merkley decided to make his name change legal to get the social network off his back.

“I filled out forms and paid 500 bucks and now I have to wait about eight weeks for a judge to approve it,” he told me over instant message. “I sent Facebook the paperwork as they requested and 24 hours later I got what seemed to be an automated response that didn’t even acknowledge the files I’d sent but instead just asked me for my real name again and said they wouldn’t unsuspend until I gave it to them.”

The e-mail he received from Facebook included the following sentence: “If you ever come across another account with a name that violates our policies, feel free to report it by using the ‘Report/block this Person’ link located on the account’s Timeline.”

It’s so sinister, it almost feels like we’re playing Paranoia. But this is real life, not a game.

Shattering communities

Many people use different identities to safely navigate living in a world where it’s not yet safe to be out as trans, gay, lesbian, bisexual, a sex worker, or to have a visible political identity, among many other completely legitimate reasons. Many of these people need the option of another identity not because they wish to harm, but because they want to stay safe. Unfortunately, because these identities are so much a part of a very real aspect of these people’s lives, many individuals within such groups don’t know one another by their legal names.

Trannyshack founder and drag performer Heklina tried to strike a compromise when her account was suspended by leaving her drag name as a first name and adding her legal surname as a last name on the social network, only to have Facebook delete her profile entirely. Because she doesn’t know the legal names of people in her community, Heklina now has no way to get in touch with her friends and support system.

This policy isn’t simply exposing vulnerable populations to harm — it’s also fracturing communities whose members often already feel alienated and ostracized in our society.

Facebook’s response

After a group of drag performers threatened to storm Facebook’s Menlo Park campus in protest, the networking giant finally caved to holding a discussion about its policy. Last Wednesday, San Francisco Board of Supervisors member David Campos and a number of performers met with Facebook representatives, but they were discouraged to find that no one attending on Facebook’s behalf had the power to alter the policy. The only promise that the network’s representatives could make was that suspended accounts would receive a two-week grace period so users could take the time to make an informed decision about how to go forward.

“This will give [drag performers and others who have been affected] a chance to decide how they’d like to represent themselves on Facebook,” said a statement from Facebook to TechCrunch. “Over the next two weeks, we hope that they will decide to confirm their real name, change their name to their real name, or convert their profile to a Page.”

Changing to a “real” name, as Sister Roma found out, may not actually require submitting an ID. According to Ars Technica, when Sister Roma input her legal name, her account immediately returned to a functional state without requiring further documentation.

“They seem to know my real name already,” she told Ars.

It’s not impossible that Facebook is using billing records for electronic birthday gifts, game credits and other purchases made through the social network to sniff out people who are using alternate identities, and to verify their real identities once these are put in.

The only option other than changing one’s account to reflect a legal name or confirming one’s name is to change a Facebook profile to a page. Unfortunately, Facebook pages are incredibly limited in terms of features. For instance, a page does not have chat functionality. A page isn’t a platform for meaningful interaction so much as it is a broadcasting mechanism — and one that Facebook increasingly wishes to monetize.

According to the social network, a page only reaches around 16 percent of its audience on average. The network claims that this is similar to the reach profiles have, but while a profile can “highlight” a post to give it more visibility, a page needs to pay in order to “boost” its content. Additionally, pages can’t initiate friend requests, initiate Facebook message threads to profiles or pages, or comment on posts on profiles — even if that profile belongs to one of that very page’s administrators.

Given the limited functionality of pages, it is unconscionable to request that non-brand entities who are using Facebook for community-building and strengthening consider switching as anything even resembling a viable option.

“We are not businesses selling products, we are encouraging our friends to come to our events and performances, promoting charitable causes, and making calls to political action, with occasional mundane daily life updates like every other Facebook user,” said the Seattle-based performer Olivia LaGarce in a Change.org petition. So far, her petition has received over 30,000 signatures.

“But maybe Facebook is not their social network if it doesn’t offer the protection that is needed,” writes Michelle Quinn at the San Jose Mercury News, who apparently sees no problem with creating a ghetto where all vulnerable populations and people who don’t meet Facebook’s standards of “real” can go live.

But even if users considered leaving a reasonable option, the two-week grace period that protesting users have received isn’t a part of this process. Before the internet rose against the policy, people were shut out from their accounts without the ability to use Facebook’s (rather limited) data export feature. There is no telling what the process will look like after things go back to business as usual at the social network. Even if users do get a few days to export their content, Facebook’s liberation tools may not include all desired content.

Additionally, it’s uncertain what Facebook means when they say “We will then ask you to verify your identity in order to help protect the security of your account,” after a user puts in a request to download profile data. If one has a pseudonym, how can they verify their identity?

The issue continues to develop. The hashtag #MyNameIs is being used for what appears to be a second chapter of the ‘Nymwars. Facebook, it seems, is only willing to copy Google Plus when it comes to features — not policy.

Header by Stephanie Doll (Flickr, CC BY-SA 2.0).

Pingback: Hey, Silicon Valley: Your Adult Policies Are Broken | /Slantist()

Pingback: Backpage: A Single Battle in A Protracted War - MiKandi Adult App Store()