The Empowerment/Objectification Duality Undermines Consent

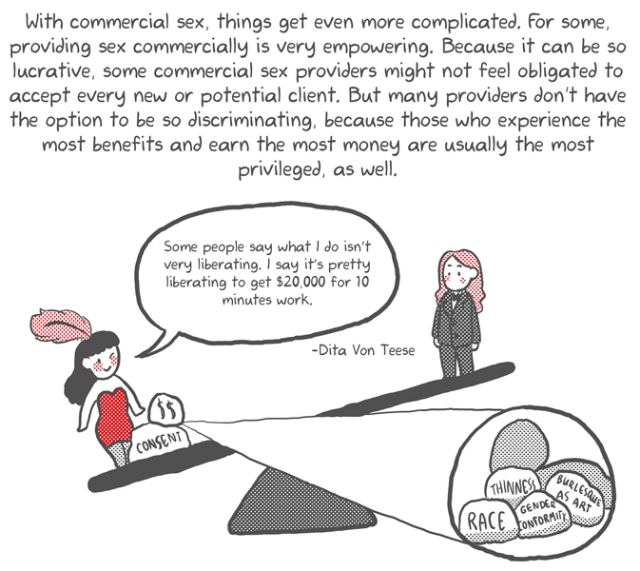

The comic “Who Has The Power: The Difference Between Sexual Empowerment and Sexual Objectification” by Ronnie Ritchie has been making the rounds since it was published on Everyday Feminism yesterday. This comic gives a straightforward way to think about the question of whether someone is being “sexually empowered” or “objectified.” It explains the two as a duality, with one being good and the other bad, and the difference being about power and consent.

The problem with this comic is that it’s both right and wrong. The right part of it is fairly obvious, but the wrong part is subtle and can be insidious. It has to do with the ways in which the comic talks about how consent can be deficient, influenced by things like financial need. It suggests (correctly) that any consent can ultimately be deficient — but it focuses this on the consent of the “provider” (i.e., the model or sex worker or simply a person Dressed In A Certain Way).

In doing so, the comic creates an insidious implication that the consent of “providers” is more deficient than other people’s consent. That’s a “magic wand” sort of argument that lets people argue that any claim of empowerment is actually false, an argument which has very nasty real-world consequences.

One easy way to see the problem is to notice that the same argument this author applies to sex work applies to anything else. Consider this quote:

Many of those who enter the sex industry as a provider may not be entirely doing so because they want to. There are a number of factors, including poverty level, race, and assigned sex. Providers of commercial sex often face enormous discrimination and criminalization, which also puts power in the hands of others besides the providers themselves.

That’s a great way to buttress claims that all sex workers are victims of sex trafficking, a common argument used for increased criminalization of them or their customers (the latter, incidentally, ends up having most of the same net effects on sex workers as criminalizing them). At the same time, the statement provides a wonderful out to explain away any sex worker who disagrees: “They’re just privileged enough that it doesn’t happen to them.”

But repeat that same sentence while talking about, say, agricultural laborers:

“Many of those who work in tomato fields may not be entirely doing so because they want to. There are a number of factors, including poverty level, race, and assigned sex. Migrant laborers often face enormous discrimination and criminalization, which also puts power in the hands of others besides the providers themselves.”

This statement is no less true. In fact, it’s true of nearly any kind of work, and that’s the key to what’s wrong here: it singles out sex as being somehow different, a situation in which consent is always potentially deficient.

This cartoon doesn’t, to its credit, take its arguments and actually pull them to that extreme. It frames the discussion so that it is easy to argue that all empowerment is really objectification — arguments which are routinely used by others to do that.

The actual flaw is in the dichotomy it suggests between “empowerment” (which is good) and “objectification” (which is bad). You should be suspicious from the first frame, which talks about the power of the “looking” person and the “looked at” person, because power isn’t a single axis — which is exactly what the comic shows later on, as it talks about financial power, cultural power, sexual desire, and so on.

In any real situation, each side will have some power, and the tradeoffs individuals are making are going to be complex. The sex worker may need the money, but he could also be working construction. His client seems to have the power in the relationship, but any business provider knows that the customer’s power isn’t actually absolute.

To be clear, I’m not saying that there is always a balance: power imbalances are real, and they absolutely occur in sex work, just like they occur in every other aspect of life. And criminalization and shaming of sex workers make those power imbalances much worse: in fact, if you wanted to analyze the real consequences of U.S. laws on sex work, you could summarize them as being optimized to maximize the vulnerability of sex workers, in favor of anyone who has the power to get them arrested, exposed, and so on.

Which is to say, there’s a real power imbalance here, but it has nothing to do with the intrinsics of sex or sex work, or even with deep things like culture: it’s something society has deliberately chosen to create.

So what’s a more accurate way of describing this? It’s to realize that “empowerment” and “objectification” aren’t opposites, but things which happen at the same time. Empowerment is about a person having agency and control over their life; objectification is about a person being viewed not as an independent subject, but as the object of a sentence, a means to someone else’s ends.

The model may be empowering herself, acquiring a source of income that she can control and developing her own independent sexuality; at the same time, the man watching her may be entirely in his own world, collecting pictures of women and fantasizing absolute control over them, while shaming the women in his life for not looking like them. Is the model empowered or objectified? The answer is that it’s both. This means that we don’t get any nice, simple lessons like “porn is good!” or “porn is bad!” which we can use to have rallies and change laws and so on.

Instead, we get the real complexities of human life.

A version of this post originally appeared on Google+. It is reprinted here with permission. Header image by Felipe Neves (Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0).